A group of First Nation elders is demanding an immediate ban on spraying of herbicides in Northern Ontario forests.

In a release, the Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) Elders Group, representing Native communities across the North Shore of Lake Huron and beyond, said it is “putting all responsible governments on notice” through a registered letter demanding any aerial spray project approved by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry in the region be “immediately cancelled and stopped.”

Raymond Owl, a member of the TEK Elders Group, said his organization is fed up after many attempts to negotiate with federal and provincial representatives on the environmental issue.

“We started this four years ago, and we’ve run out of patience,” he told Postmedia. “We’ve had demonstrations; we’ve tried to negotiate. But it’s like talking to a rock.”

Owl said the application of herbicides on traditional lands to promote the growth of replanted forests “comes down to a treaty issue,” as First Nations inhabiting the Robinson-Huron Treaty area were “never consulted on spraying.”

The Robinson-Huron lands span a vast area, including North Bay.

“It’s about five million acres, from the height of land to Lake Huron, and from Sault Ste. Marie to past North Bay,” said Owl.

Foresters argue the chemicals used to knock down inferior species competing with planted conifers are less toxic than table salt and won’t impact insects or mammals, but Owl and his fellow elders believe the herbicides kill far more than weeds.

Owl said ongoing issues of bears coming into communities to scavenge for food may well relate to the destruction of natural foods in sprayed areas.

“You might see lots of blossoms on the blueberries but it takes a bee to pollinate the flowers, and if they’re getting killed, you don’t get the berries,” he said. “A bear will only eat grass for so long. That’s what brings them into town, because they have nothing to eat.”

Owl added it’s not only First Nations people who are concerned; many non-natives who have camps adjacent to reforested areas, or who hunt and fish on Crown land, have also expressed alarm at the spraying and reached out to his group in solidarity with their cause.

“We also have support from five municipalities along the North Shore,” he said. “Massey gets its drinking water from the river, and they’re spraying farther north, so that’s a concern for them. But the province won’t listen to them either.”

The elder said a meeting of First Nations leaders was held recently in Cutler, on the North Shore west of Massey, and his group received the backing of the Union of Ontario Indians and Assembly of First Nations to be the lead on the aerial spraying cause.

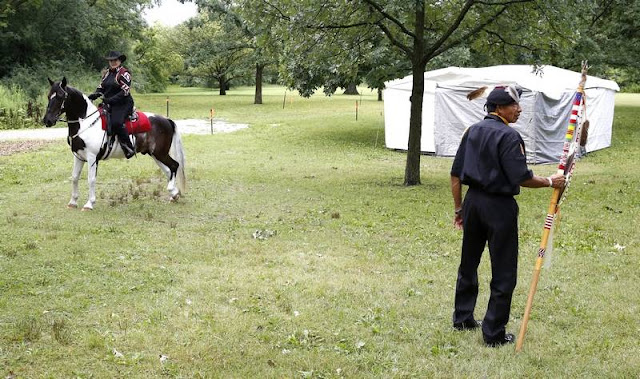

If spraying goes ahead in the meantime, the Ojibwe elder said his people have information on which blocks are identified for herbicide treatment, and will make sure there’s a human presence there to disrupt the undertaking.

Indigenous peoples in what is now Canada collectively used over a thousand different plants for food, medicine, materials, and in cultural rituals and mythology. Many of these species, ranging from algae to conifers and flowering plants, remain important in today's indigenous communities. This knowledge of plants and their uses has allowed Aboriginal peoples to thrive in Canada's diverse environments. Many traditional uses of plants have evolved to be used in modern life by indigenous and non-indigenous peoples alike.

Source

In a release, the Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) Elders Group, representing Native communities across the North Shore of Lake Huron and beyond, said it is “putting all responsible governments on notice” through a registered letter demanding any aerial spray project approved by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry in the region be “immediately cancelled and stopped.”

Raymond Owl, a member of the TEK Elders Group, said his organization is fed up after many attempts to negotiate with federal and provincial representatives on the environmental issue.

“We started this four years ago, and we’ve run out of patience,” he told Postmedia. “We’ve had demonstrations; we’ve tried to negotiate. But it’s like talking to a rock.”

Owl said the application of herbicides on traditional lands to promote the growth of replanted forests “comes down to a treaty issue,” as First Nations inhabiting the Robinson-Huron Treaty area were “never consulted on spraying.”

The Robinson-Huron lands span a vast area, including North Bay.

“It’s about five million acres, from the height of land to Lake Huron, and from Sault Ste. Marie to past North Bay,” said Owl.

Foresters argue the chemicals used to knock down inferior species competing with planted conifers are less toxic than table salt and won’t impact insects or mammals, but Owl and his fellow elders believe the herbicides kill far more than weeds.

Owl said ongoing issues of bears coming into communities to scavenge for food may well relate to the destruction of natural foods in sprayed areas.

“You might see lots of blossoms on the blueberries but it takes a bee to pollinate the flowers, and if they’re getting killed, you don’t get the berries,” he said. “A bear will only eat grass for so long. That’s what brings them into town, because they have nothing to eat.”

Owl added it’s not only First Nations people who are concerned; many non-natives who have camps adjacent to reforested areas, or who hunt and fish on Crown land, have also expressed alarm at the spraying and reached out to his group in solidarity with their cause.

“We also have support from five municipalities along the North Shore,” he said. “Massey gets its drinking water from the river, and they’re spraying farther north, so that’s a concern for them. But the province won’t listen to them either.”

The elder said a meeting of First Nations leaders was held recently in Cutler, on the North Shore west of Massey, and his group received the backing of the Union of Ontario Indians and Assembly of First Nations to be the lead on the aerial spraying cause.

If spraying goes ahead in the meantime, the Ojibwe elder said his people have information on which blocks are identified for herbicide treatment, and will make sure there’s a human presence there to disrupt the undertaking.

Indigenous peoples in what is now Canada collectively used over a thousand different plants for food, medicine, materials, and in cultural rituals and mythology. Many of these species, ranging from algae to conifers and flowering plants, remain important in today's indigenous communities. This knowledge of plants and their uses has allowed Aboriginal peoples to thrive in Canada's diverse environments. Many traditional uses of plants have evolved to be used in modern life by indigenous and non-indigenous peoples alike.

Source